Bruce Mau is a designer, a revolutionary, and a visionary. During the last 15 years he and his studio have worked collaboratively with well known clients, designers and leaders in the creation of projects that shape our future and redefine our world and our way of living. His work involves constant search and experimentation; broad, collective and interdisciplinary.

In this interview, Mau discusses how we live and the structures we have created to support our life styles. He reminds us that “design is invisible until it fails” and calls for rethinking the role of design in creating the good life and in shaping a better future. He discusses the underlying and unavoidable links between design and economies that must support and sustain nine billion souls.

CATALYST: Thank you for meeting with us Bruce. We would like to invite you to explore the good life with us and the role of design in shaping it.

What comes to mind when you think of “the good life”?

BRUCE: That’s a great question. I think that you have to imagine a new definition of good, because one way of defining that is really part of the old way of thinking, is a kind of excess of luxury, or consumption. We need a more intelligent way of being in the world.

We need to think about using less energy not more, consuming less not more. It is not about having a worse time or having less of an experience, but rather about having more of an experience and less of an impact.

CATALYST: What role does lifestyle play in this more intelligent way of being in the world?

BRUCE: Well it is important to note that it is actually two words, “life” and “style”, and not the singular, one word term that is again generally considered to be about consumption. If you think about style, there are some people who think style is not a serious subject, not something that is worthy of serious consideration. But in fact, philosophy is style. Style is a way of living, a way of being. So, when I put together my book Life Style I was really trying to understand, “What is our way of living? What is our way of being?” In other words, “What is our style of life?”

In trying to understand life style in a new context, I realized that what is going on is extraordinary. We have an amazing capacity to realize our own potential–just absolutely off the charts. Throughout history who had the capacity that we have as individual citizens today? For most of history, almost everything that we are capable of was out of the reach of even the most powerful rulers.

But now, we have capacities that kings and queens and leaders could have not even imagined. That requires a new conversation about those possibilities and the philosophical issues, questions and dimensions that they challenge us with, and introduce us to.

CATALYST: Do we also need a new conversation about the relationship between style and design?

BRUCE: Well, I think style can also be positive or negative; you can have a “hideous style”, not only visually, but also in its conception.

To produce a deliberate style that is not accidental, that isn’t a consequence of random effects, there is only one way to do that, and that is by design. It is a process of understanding that I want a particular outcome, not random outcomes, and therefore I intend to design it.

CATALYST: We are also really interested in how you tie design with economies, and other concepts you discussed in your books. So, if you say that the future demands a new kind of designer, what qualities, tools and skills does this new designer need?

BRUCE: That’s a great question. If you think about design in this new realm, if you think about designing a new way of being, designing a way of living, it’s not necessarily a visual outcome. It’s not necessarily an object-based outcome.

It’s really about thinking about the often-invisible systems that are supporting our way of living. It’s thinking about the context in which we are living, as an ecology that sustains process.

So you need a very different sensibility. First of all, you need the tools to understand systems. You need the tools to understand different scales of operation, that if you’re designing an object, that object is not a discrete entity. That object is actually incorporated in other systems, and the object itself incorporates systems within it.

So the idea that somehow you could have a thing that is separate and discrete from the context in which it exists in is a kind of fiction that we have produced in order to get our work done.

The reality is that the objects that we produce are tied into complex webs of relationships, with the ecology and the context that they are part of, which will demand a different set of abilities, tools, ways of thinking, and the ability to move across scales, being able to look at the big picture. Zooming out and looking at the big picture of the economy and ecology of a project, zooming in and looking at almost an atomic level to understand the matter and the energy of a project. And then, being able to communicate at those different scales, what’s going on and how we put things together.

Obviously that is a very different approach and I have to say that it has been really challenging over the last several years. For me, I have more or less worked this way, organically, from the outset, with a kind of sensibility and proclivity that I have to think about those kinds of things. But I have to say that it’s been a real challenge in the market. Most people don’t see design that way, and most companies don’t see design as something that you apply to the business, not to the products. They see it in a very particular way, in a very conventional way. I’ve been fortunate to find people along the way, who really wanted to engage in this other level. But it’s been quite challenging to articulate it even, to say, “This is how I see it, and this is how I want to work”. It’s very different from the conventional way.

CATALYST: That being said, we also want to ask you, in your Incomplete Manifesto for Growth, you said that “everyone is a leader”, and in Massive Change and also in The Third Teacher, you said that “everyone is a designer”. For you, what is the relationship between designing and leading?

BRUCE: In some ways, designing is leading; design is leadership. You can’t design, except to envision a new world. I don’t think there is a better definition of leadership. For me one of the most interesting developments in this way of thinking about design is that the leadership of governments becomes a design project. The leadership of business, of organizations, within your own life, these become design questions. If you want specific outcomes, that is design. If you want something other than random events in your life, you are in some way designing that.

The idea that everyone can be a leader is really about understanding that leadership isn’t something that you earn by tenure; it’s not something that you have because you’ve been here the longest. We should be open to leadership across the spectrum of experience. I’ve had this experience myself, I did a huge project in Japan, and the youngest guy in the studio led that project. He went to Japan and met with one of the most powerful developers in the world, in Tokyo; here’s a young guy, just out of college, leading a project, collaborating with one of the most powerful people in Japan, and it was amazing. He just had what it took at that moment to lead that project.

The idea that somehow the hierarchical, chronological orders to leadership is not the new spirit.

CATALYST: Just to add to what you were speaking about previously, you are one of the few leaders who is advocating so much optimism. What do you see is the relationship between optimism, politics and design?

BRUCE: Another really good question. One of the challenges about being optimistic is that you look like the village idiot. People are so often battered by constant barrage of negative images, negative stories, and the worst of human behavior, that it’s no wonder that people are pessimistic. One of the ways I’ve described this is, if you published a newspaper called reality, it would be a mile thick, and the first quarter inch of it would be the New York Times, and it would scare the living daylights out of you. You would just want to hunker down, lock your doors, close the borders, and be defensive in every way. But the rest of the mile is massive change. The rest of the newspaper that is a mile thick would be things like, “here are people at Northwestern University who are collaborating to invent an AIDS test that costs less than a dollar and gives you the results in under an hour”. You’re not going to hear that story because no one’s going to get hurt by it, no one’s going to get killed by it, you’re not going to hear that story.

I think one the great challenges of our time is to actually see the reality of what’s going on. The reality is that we’re almost seven billion people. If we were failing, we would be one billion. The fact is that most of the challenges that we face today are the challenges of success, not failure.

The great problems that we will face in this century are the problems of succeeding. That we are going to be seven, eight, nine, ten billion people, and that we are going to face the challenge of feeding them, sheltering them, connecting them, allowing them to reach their full potential.

When I think about my own optimism, it’s a fact-based optimism. If we were a billion people, I’d be pessimistic, and rightfully so. But the reality is that it’s probably the greatest moment in human history, to be alive and working, where more people in more places are participating in new forms of wealth and possibility than at any time in human history. By a radical long shot not by a margin. Billions of people have become wealthy; now that is causing new problems, but that is a wonderful problem to have. And we still have great old problems, like the people at the very bottom of the pyramid, in poverty and needing access to possibility.

CATALYST: Some of the challenges that you described in Massive Change are about those seven billion people, so you referred to them as citizens. You also have discussed the need for designers to design from the perspective of the citizen. That would include both sets of people. How do you think designers can be enabled to do this?

BRUCE: Well, when I was quite young I thought of myself as putting out a signal. That I needed to broadcast a signal that other people could find. There are many people who see people as citizens and not consumers; unfortunately they are not the majority at this moment in history. I could tell you the number of times when I’ve been in a room and people have referred to the population as citizens and not consumers; almost every company thinks of people as consumers. To change that, you need to actually think about this way of working and thinking for yourself, and think, “What am I doing to understand the individual and their possibility as a citizen? And then I need to broadcast that signal in a clear and pure way, so that other people can find me, because I need to find the other people who also want to work this way.

When I was young and started out first working in design, I realized that the kind of interests that I had were really esoteric and not too many people would be right for me to work with. It was really critical to maintain clarity of signal so that they could find me, because if I were doing something that confused or compromised that signal, they would not be able to find me.

I think a really important aspect of a design practice and being a designer, is to understand that you have to actually take responsibility for that signal.

CATALYST: Do you think the future of design lies in redesigning economies?

BRUCE: I certainly think that’s a huge issue, and challenge that we face. So, if you think about the way that we do things as an economy, in other words, if we’re making things and exchanging things, that’s an economy. The way that we’ve designed the economy determines what gets exchanged, and what has value. In business there’s an idea that whatever you measure is what you value. If you want people to do certain things, then you have to measure that thing in order that they know that that’s what you’re actually interested in. We’re working with a group right now, and they have time sheets. And we said, well, “Why don’t you have idea sheets?” If you believe in ideas, why would you have time sheets and not idea sheets? Are you really saying that it’s all about labor by the hour? Or do you believe in the value of ideas? If you do, then you need to redesign that economy, and begin to understand how do we actually quantify it, measure it and therefore value it, and communicate that value and build a new economy around that new value.

CATALYST: In your book Life Style, you talk about the Global Image Economy. I wonder if you could please elaborate on the meaning of that.

BRUCE: What we realized was that there was a new kind of context. If you think about the image as a practice, there’s a wonderful book that Phaidon produced called 30,000 Years of Art. They just selected some of the most beautiful images and artifacts from around the world, in all different cultures over 30,000 years, and put them in chronological order. So you can see, what’s happening in Japan, at the same time as something else that is happening in Central America. And, what you see that’s really interesting is that, for most of history, images were actually objects.

There’s a huge transition that happens sometime over the last thousand years or so, and accelerated in the Renaissance, where you move from the object to the image. But there’s no capacity to reproduce that image. So each image is a unique entity, and over time we developed the capacity to do absolutely amazing images at increasing scale, and to create these extraordinary images of exceptional power. The development of image distribution begins with Gutenberg, and earlier in China, where we introduced the first notion of reproduction. What happened over the last century, especially over the last fifty years is that the capacity to reproduce runs like wildfire. What I realized is that this is actually in the process of generating a new context within which we work.

If you think about who owns the power of the image, for most of the last five centuries, it was the church. So almost all the images in the 30,000 years of art over the last five centuries are images from the religious works of one sort or another. And they controlled the image, and if you wanted to experience one, that’s where you went, they saw the power of it. Now it’s a radically democratized potential. My daughters do videos like I did drawings with pencils. They have the capacity to use the image and generate new expressions in a way that, when I was a child, would have involved a Hollywood studio. I call it “cinematic migration,” and that distribution of the economy of the image is producing all sorts of new behaviors, economies, possibilities, and so on.

CATALYST: What role does the Global Image Economy play in the relationship between business and design?

BRUCE: If you think about producing a product today, if you have a business, you have an image business and a design business, or you probably won’t have a business for long.

Every business today is a design business, or it won’t be a business in the future. It’s about designing new possibilities, and the capacity to visualize those potentials is central to future business.

And that puts design and visualization and the image economy right at the heart of new business. So, if you think about the proliferation of images, and the competition of images for attention, you realize that it’s unbounded in its voluptuousness, in its capacity to produce new and beautiful things, and sometimes also horrific things.

But the capacity to generate visual culture grows daily, and that means that the competitive context in which you’re working is that new image context, that new image economy. Ultimately, if we’re producing 100 billion images a year, and if you’re creating a new thing, if you’re producing a new image of a new way of living, a new idea or product, that means there’s going to be 100 billion and one. And that ‘one’ has to survive in that context of 100 billion.

CATALYST: Also in your work you spoke about the importance of a collaborative process, in particular the use of renaissance teams and the redefining of the relationship between the designer and client. Why is this so critical for you?

BRUCE: Design is still very much thought of as a singular cultural practice, in other words it’s about authorship; it’s about a single individual doing a single thing. So, the whole world of wonderful products and beautiful objects ties us back to that understanding.

The reality of most great challenges that we face today is that the likelihood that an individual can develop the capacity to solve it is almost zero.

The likelihood that a person has the renaissance ability to master multiple bodies of knowledge is really not plausible. If we’re going to take on these challenges, what that suggests is that we have to develop new models for how we do that; that if we simply go at it in the old way, “I’m smarter than the last guy”, then it’s going to be a setup for failure.

One of the things that we discovered in our own practice, it was actually Bill Buxton who is a lead researcher for Microsoft who saw it, he said what you’re actually doing is putting together a renaissance team, because the renaissance person is no longer possible. Ultimately, if you’re going to take on these challenges, you’re going to have to assemble a team that has science, art, design, culture, imaging, cinema, writing, poetry; ultimately you are going to want to assemble a team that has a great diversity of talent and skill to be able to tackle the problem, articulate the problem, speculate on solutions, analyze solutions, and really formulate new strategies. That was where that concept came from, but we had already developed this organically in our own practice; you’ve got to put together a group of people if you’re going to have any hope of dealing with these issues.

CATALYST: Some of the challenges you mentioned, and identified in Massive Change. You also identified several Design Economies, as you refer to them. We were curious as to how those Design Economies relate to the Global Image Economy that you outlined in Life Style?

BRUCE: The notion of a discrete economy is not really plausible. In other words, we identified ten design economies – energy, movement, the economy of the image, the market economy – and the way that we defined those is as realms of your experience or of your world that are being reinvented or invented by these new capacities to design.

If you imagine the number of times that you can close your eyes, and open them in a space where you only see natural things, you realize that it’s almost zero. You live inside of a complex set of design economies, and most of your experience is designed. You live a designed life.

Now much of that is really badly designed, but it is designed nonetheless. It is produced for you. Much of it is also extraordinarily well designed, or beautifully designed. But your experience is inside of these design economies. So what we tried to understand was, what are they? How could you define them? It’s not that they’re ultimately discrete, in other words, the economy of movement in some ways is an energy economy. It’s about what forms of energy we use to create movement, and the experience that results from that approach. So in that sense, they’re not meant to be seen as discrete.

The image economy is just one section; every one of the other economies lives in some ways within the image economy, in the same way that they live within the market economy. It’s a complex set of interrelated economies. You just can’t imagine an economy of movement divorced from the image economy.

CATALYST: We are very interested in what Japan might teach us in what ways an economy might change, in what ways it needs to change. Do you have any thoughts about what we can learn, based on the most recent experience of natural disaster in Japan, and how Japan is working with that experience?

BRUCE: There are a number of lessons. I have to say that I found the whole episode extraordinarily revealing and horrific in many dimensions, but also challenging in many ways, and I would say inspirational in many ways. In the sense that, on the one hand, obviously the impact on the people and the sheer force of the natural world was absolutely extraordinary, I mean I’ve never seen anything quite like it. But at the same time, when you think about how resilient their systems are, in that context, that even with the absolutely amazing force of impact, and there are a staggering number of people who actually lived through it, and survived it. If you think about the level of design in that country, the level is so high that they could actually experience an earthquake at that magnitude and mostly survive, when in countries where you just don’t have that caliber of design development, the death toll would have been orders of magnitude greater.

At the same time it also reveals some fundamental challenges in the systems that we’re designing, especially in the nuclear system. You’re kind of balancing a can of kerosene with a candle on top of it, on something that is extremely fragile; that is in fact volatile in movement and motion. So the potential for disaster is there in such a big way.

I think that in some ways the disaster there exposed the potential that we have in many places around the world for that kind of impact. At the same time, you have to realize that for the most part, the industry has been extraordinarily safe; that we’ve been producing this kind of energy with almost no disasters, over decades. I’m just trying to understand, what does a post-crisis economy look like?

I think that it’s a really important series of investigations, because I think at this moment, we still only have one definition of a successful economy, and that is growth. If you listen to any day-to-day economic news, we can’t imagine an economy that is producing less, as a successful economy. We can only think of it as producing more.

I think that the challenge there is, how do we define ‘more’, in a way that isn’t a greater impact? That doesn’t demand more and more resources, and take away from the future of our children? Or leave them a bill, a toxic legacy in the way that we do it? And I think that’s a huge challenge as it is, about as big a challenge as we can imagine. What we have to do on top of that is, how do you do that in a way that is actually ‘growth’ more in greater possibility, and not defined in the negative, so that it isn’t defined as a future that is less than our past. Because so long as it’s defined that way, people will move away from it, they’ll move away from that kind of intelligence. No matter how brilliant it is, if it looks like sacrifice, they will move towards something else.

And though there will always be a group of hard-core, environmental thinkers who are happy to sacrifice in order to accomplish a new way, ultimately we have to get beyond that to a model that is not about sacrifice but is actually about a better experience, one that is more beautiful and more exciting.

I think that if ever there was an opportunity for a different way of thinking, and really exploring that possibility, it’s in a post-crisis condition.

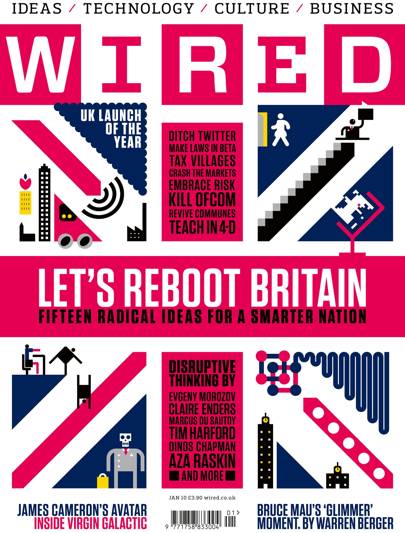

CATALYST: It’s such a good example of when you say, “design is invisible… until it fails”, all of us watched the same images and watched design fail, and succeed in so many ways, so, thank you for the thoughts on that. Thank you for broadcasting your signal so clearly that we were able to pick up on it.

BRUCE: Thank you so much, truly. Very insightful and demanding questions.

CATALYST INSIGHT:

– Design requires collective, interdisciplinary, and collaborative teams capable to understand the systemic dimension of every object and the interconnectivity between the systems that support our way of living.

– Re-designing a new economy requires that we understand our way of living, redefine our concept of good life, and ultimately re-formulate our societal values.

– The design challenges of our time represent our success and flaws as a human race. They bring to us an opportunity to reach our potential as a society with possibilities never seen before.

– Design is far from isolated object outcomes. Design is about the collective visualization and creation of new possibilities of change that allow us to successfully face the challenges of growth.

STRATEGIES IN ACTION:

– Imagine a new definition of good life.

– Understand our capacity to realize our potential.

– Open a new conversation about our new possibilities and their challenges.

– Understand that particular outcomes require a design intent.

– Think and understand the role that every object plays within the invisible system that supports our way of living.

– Open to a new understanding of leadership that is not chronological or hierarchical.

– Face the challenges of success.

– Think about citizens instead of consumers.

– Build a new economy based on what society really quantifies, measures, and values.

– Design and visualize new possibilities for business.

– Design new collaborative models to solve the challenges of our time.

– Redefine a positive economic growth that gives to the future generations a greater experience, full of possibilities instead of sacrifices.

About the Author:

Bruce Mau is founder of the Massive Change Network. Mau’s clients included Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, MTV, Arizona State University, Miami’s American Airlines Arena, New Meadowlands Stadium, Frank Gehry, Herman Miller, and Santa Monica’s Big Blue Bus. Through his work, Mau seeks to prove that the power of design is boundless, and has the capacity to bring positive change on a global scale. Working with his team of designers, clients and collaborators throughout the world, Mau continues to pursue life’s big question, “Now that we can do anything, what will we do?”